CONVERSATION CORNER – Part Two – Lest We Forget – The Survivors

by H. Naomi March, M.A.

Remembering Victims and Survivors

Last month, this column re-visited personal memories of Christchurch, and the ninth anniversary of the February 22 earthquake, remembering our losses, our resilience, and our efforts to recover such traumatic times while rebuilding our city and our lives.

This month – sorrow upon sorrow for Christchurch – is the first anniversary of the horrendous slaughter of our people, at prayer, right here, in our quiet community – Friday Prayers, 15 March, 2019. The number killed – 51 – blazed into our brains by repeated media reports.

But – 100 people were torn into – each one wounded multiple times – with bullets from military-style semi-automatic weapons and assault rifles!!

What about the 49 victims who were shot, and survived that horror? What about those who witnessed the carnage, but were not physically injured? They will still have to live with those memories, if not the physical pain. What about the little children? Will they all thrive? What about grieving families and friends? Do we remember they are still struggling – not just with grief, but life’s practical problems?

Remember the heroes who rushed to the scene – police and ambulance officers reported walking through “rivers of blood” to get to the victims inside the mosque – and the hospital staff in all categories, working for hours on end, days and nights, exhausted, and heart-broken by what they saw. Some of these heroes now have PTSD, including the symptom of regular nightmares! What about neighbors who risked their lives to help strangers? And remember, too, countless people who experienced psychological impact.

Victims sometimes have a long process to go through, before they can be called survivors. Some who survived the shooting, died en route to hospital – others died in hospital. Others underwent difficult surgeries, and some still need more operations, to remove shrapnel that is leaching lead into their bodies and poisoning them, or to further mitigate debilitating injuries. Think of those who fear sitting outside, or going to the shops, or going to prayer. I know an older woman – not connected with our Muslim community – now afraid to go shopping, because of the fear of terrorist attack.

I would need to write a book – not an article – to include all of the suffering, and challenges, and courage, and community responses. But my goal here is to have us pause, and remember the survivors of many types of tragedy, in our city, and the world at large – who were first victims – and try a lot of kindness with each other, to help them survive, and thrive. Please reflect on this thought – not all victims die, and not all survivors live.

Loss and Grief

Memorials, by nature, remember the dead – those we lost to war, lost to natural disaster, lost to crime, or other causes. Memorials don’t usually remember the victims who survive! We do not hold special services for those survivors. Perhaps it is time we did so, because they live with the aftermath – for generations to come.

Next month – April 25 – we hold our annual commemorations to remember the WW1 ANZACS – and all other military personal in conflicts since then – who died for our freedom. But what about the ANZACS who returned home physically wounded &/or shell-shocked – now recognized as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) – who suffered, and survived? What about those who brought their nightmares home to their families – not in words that could be understood, but in actions that could not? Immediate family members – and their descendants – became ‘victims of war’ too, because sometimes the generations that follow, continue to be impacted by changes in family function, which is often overlooked, or not understood.

And what about civilians caught in war or genocide – who need to flee their homeland to find safety? Others seek sanctuary so they may worship according to their beliefs and conscience. These were our citizens massacred while praying – some were refugees, while others were immigrants, and still others were holiday-makers.

Further examples include stories of Holocaust survivors who didn’t tell their children about the horror they survived – or their heritage – afraid that history would repeat itself if their descendants knew their true identity. Think of 9/11 in Washington D.C. and New York City – a woman who escaped the burning Towers before they collapsed, wasn’t diagnosed with PTSD for 18 years. Even though symptoms weren’t present for several years, when they came, she hadn’t made the connection, because, in her mind, she hadn’t been a first responder.

And of course, last month’s earthquake memorial here in Christchurch. It doesn’t take a war to leave someone with PTSD. Surviving a natural disaster can cause it, as can the trauma of ill-health – which might include the loss of body-image &/or function, and facing possible loss of life. I think of the CTV staff who are only alive because they were not in the building – imagine a couple of young crew members – crossing the road on their way back from lunch – seeing the building collapse right in front of them – killing their colleagues, who felt more like family than friends. Had they been 12 seconds earlier, they would have died.

Only Maryanne was standing near enough to CTVs large glass doors, so that she was miraculously able to force them open as they buckled – the only staff member to make it out alive – she became the face and the voice for those we lost – and a fighter for justice. That’s a lot to live through, and live with.

And these CTV survivors confirm what research has found, and I know it myself – trauma never fully leaves us. We can recover to a great degree, and even function well – but every now and then it floods back with a bang, and then leaves us to pick up the pieces, and carry on living. They are also well aware that as survivors, they have been mostly forgotten.

We also know that surviving crime can have the same affect on victims – one example I learned of was that PTSD was found in full symptom criteria in 94% of female rape victims, one week after the event. However, specialists have found that observing a crime can do damage, too.

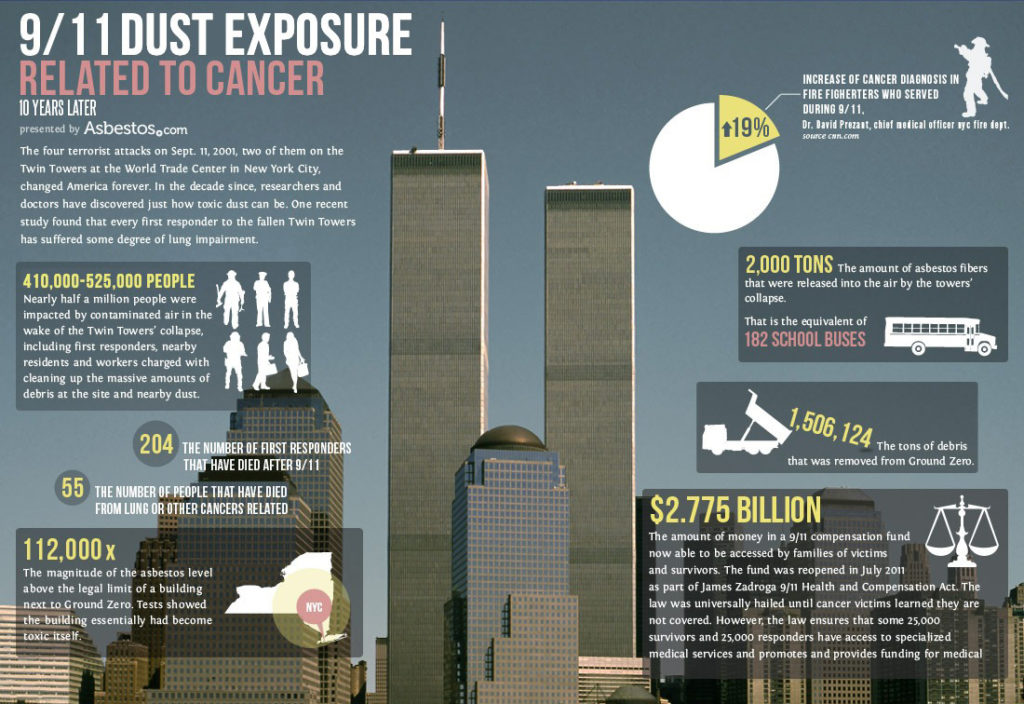

Researchers have discovered that symptoms of stress from surviving trauma can occur years later, set off by a trigger in the present – a sight or sound that reminds someone of the event – can set off PTSD. A lot has been learned over the last 18 years, since September 11, 2001. Physical illnesses are also being connected with the 9/11 survivors, first responders and Ground Zero site workers.

Thankfully, not everyone who survives trauma – military or other events – suffers psychological or physical injury, or if they do, they recover quickly. But – lest we forget – spare a thought for the many who do not recover quickly, or who struggle in a number of ways, including financially, socially &/or spiritually, or who have suffered betrayal trauma, such as child sexual assault by a family member, or close family friend, or religious leader.

The thread that ran throughout my lectures with American Professor Beverly Hislop, was the fact that pain, loss and grief underlie any type of trauma or crisis. Whether PTSD is present or not, grief follows loss, and most of us need support, if we allow grief to run its course – we are all human, and it’s our nature to give help, and receive help. Tragically, too many people are able to override this aspect of their humanity while they discount the humanity of those they violate. This attitude of superiority and entitlement is getting worse, worldwide.

On pages three to nine of “The Grief Recovery Handbook” (2009) John W. James and Russell Friedman defined grief as “. . . the normal and natural reaction to loss of any kind, [and although] the most powerful of all emotions, it is also the most neglected and misunderstood experience, often by both the grievers and those around them.” Along with death and divorce, they also identify forty “common life” experiences – e.g., moving home, financial changes, loss of heath &/or employment – as well as loss of trust, safety and control of one’s body – due to sexual or physical abuse – which society does not recognize as “grief issues.”

They believe – after 25 years in this field – that all efforts to heal the heart with the head fail because the head is the wrong tool for the job. It’s like trying to paint with a hammer – it only makes a mess. Of great concern to them is the observation that incomplete recovery impacts a griever’s life negatively, and “over time the pain of unresolved grief [repressed emotion] is cumulative, [and] may doom the future,” because whatever the loss, unresolved grief is the primary issue.

Every instance of loss and grief is unique, even the same shared loss – because each person suffering the loss of that person, or thing, or circumstance – experiences it through their own uniqueness. Each man killed at the mosques might have been someone’s father, husband, brother, friend, uncle, or each woman could have been someone’s mother, wife, sister, cousin, and the children – lost, and no-one else can ever replace them. Yes, people can remarry, or have other children – but they are new people in their lives, not replacements for those that were lost.

For some citizens, the sense of safety has been lost, their innocence shattered – such is the aim and impact of terrorism.

Normal Crisis Pattern is Different to Trauma

I am neither a trained nor a qualified counselor. My Master of Arts degree is in Pastoral Leadership – with emphasis on Pastoral Care to Women. During those studies, a course on Crisis Intervention was mandatory, and I share the following based on lessons learned in lectures – and through living life – because I found it helpful.

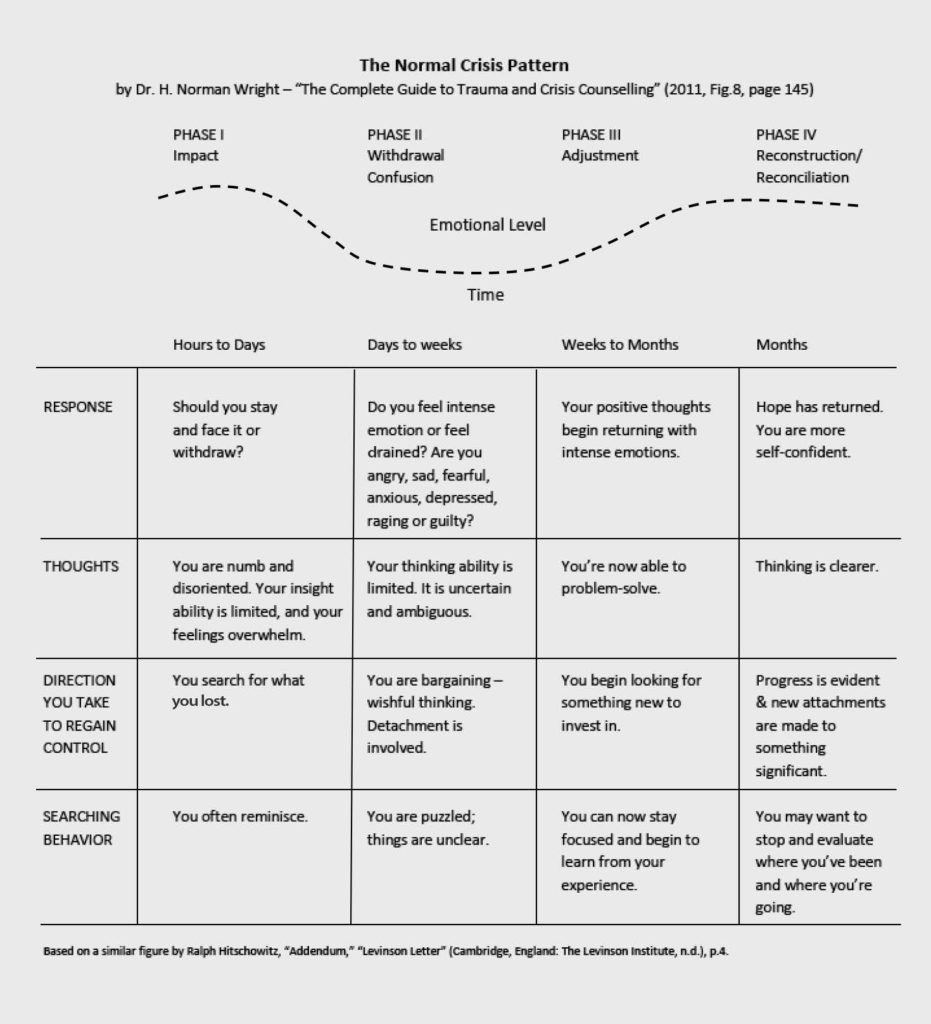

From my textbook “The Complete Guide to Crisis & Trauma Counseling” – written in language suitable for the general public – I have included here, “The Normal Crisis Pattern” that I studied in 2014. On reading it, my first reaction was, “Oh, thank God. I’m not going mad. I’m normal for someone going through a crisis.” Honestly, I had been stuck for three years, post-quake, due to lack of intervention and moving away to find somewhere to live. Returning a few years later, I had missed certain processes the city and our citizens went through for healing.

After studying Dr. H. Norman Wright’s pattern, I moved up a Phase overnight, because being able to recognize it as normal behavior, freed me to move. I realized I had been suffering what Wright calls “paralysis of the will.” Recognizing where I was stuck, and where I wanted to go, freed me to continue moving forward over time.

In chapter eight of his book, Wright is very clear that while loss and crisis are found together, trauma and crisis are different. Since research and experience show that a crisis ends within a maximum of six weeks, help needs to be available during this brief window of opportunity, and Wright lists the types of interventions that will support positive outcomes. Initially, I failed to notice the curve of the emotional level over time in the pattern, but clearly, by the end of Phase IV, the levels are not equal – hence the saying, “a ‘new’ normal.”

After experiencing the benefits of this knowledge – knowledge has power when applied – I practiced my Winter School presentation on my fellow Toastmasters Club. Its effectiveness was evident in members’ facial expressions during the presentation, and from their feedback afterwards. The relief was similar to my own – “We’re not going crazy! We’re normal for people who have suffered such traumatic circumstances.”

However, trauma, as Wright explains in chapters ten and eleven, “… is more than a state of crisis. It is a normal reaction to abnormal events that overwhelm a person’s ability to adapt to life – where you feel powerless.” It is normal for people to experience emotional aftershocks once the trauma is over, and sometimes they are experienced months, or years later, depending on the severity of what happened. By giving or receiving support and understanding, a stress reaction can pass more quickly. If the event is too painful for someone to manage alone, or even with family or friends, it is important to work with a professional counselor – trained in trauma-focused care – which is not a sign of weakness, but a sign of strength, by admitting the need of assistance. Research shows the timeframe for trauma is much longer than that of a crisis. When all else fails – keep reading the instructions – which I had failed to take in at the time. It makes sense to me now – trauma can take a long time to heal, depending on its force, and the situation of the person suffering it. Tenderness towards each other can be a powerful tool against trauma.

Remember the outpouring of communal grief, and love, and support – flowers, finances and friendship with practical assistance – we saw in Christchurch, last year? The worst of human behavior witnessed here, that lasted minutes, was drenched by the best of human behavior that lasted days, weeks and months. There is strength in giving and receiving comfort, which also contributes to our well-being, and builds resilience.

Resilience and Comfort

Psychotherapist and author, Amy Morin – in an article for Forbes – listed seven scientifically proven benefits for practising gratitude – a known precursor for resilience. Gratitude: increases opportunity to more relationships; improves psychological health; improves physical health; reduces aggression and enhances empathy; increases mental strength; improves self-esteem; and grateful people sleep better.

A common method of maintaining gratitude is to keep a journal – in which a number of things can be recorded and thought through – including things we’re grateful for. When I was working on my post-graduate degree, I found myself all “written-out” from note-taking in lectures, and massive assignment writing. So I purchased a specially designed ‘gratitude journal’ with space to briefly record three things I was thankful for each day. It was manageable and less stressful than staring at a blank page – it had limited room to write short, sharp, sweet entries – and I could pick it up, be quick, and put it down. It was not a ‘chore’ and it saved my sanity during my studies. Researchers have found that being grateful for three things a day, builds resilience.

I am intentionally learning to accept that suffering, and overcoming it, has meaning when we use those experiences – and the knowledge gained through reflection – to help us understand such all-encompassing suffering felt by others. The comfort we have received is the comfort we can then share, with another.

From a spiritual perspective, friends have comforted me with the idea that I have been ‘trusted’ with various types of losses in my own life, including times of poverty and poor health, along with other, unspeakably traumatic events – which I can add to my observations of life through nursing, teaching, ministry and post-graduate education – to gain a broader spectrum of understanding, and compassion, for our human condition.

This has not been an easy attitude for me to accept, because it requires forgiveness and gratitude – vital keys to being resilient. The number of times many in our Muslin community have voiced their willingness to forgive, and their gratitude for the Christchurch community’s support – yet I fully understand those that still struggle with hatred towards the perpetrator of this hate-filled, evil crime, who so callously and methodically robbed them of their families, friends, productiveness, and peace of mind. Time alone does not always heal – intention, and action, often with help, is needed – and it’s hard work for most of us.

By ensuring our own physical and psychological healing – with carefully selected professionals, when necessary – means we are not only resilient for the next crisis in our lives, we are also ready to support our community should another disaster strike. It’s like packing gratitude, resilience and forgiveness skills along with the clean drinking water, dry clothes, dry food supplies, first aid kit – and all the other necessary things on our personal emergency evacuation list. There is definitely something special about being strong enough – and prepared – to supply support in a crisis, because you’ve taken care of yourself, and your own, first.

Compassion and Kindness

Christchurch community poured out compassion – not just with floral tributes, but also time to listen, driving victims/survivors where they needed to be, and the whole nation joined us by contributing financial support, and holding candle-light vigils. Food was provided – with the reminder to respect Halal Food Laws and Practice. I joined the women who wore head scarves a week later, and I admit to being somewhat afraid, as I went about my day in the city.

The Prime Minister added to her duties as our elected leader, by providing the kind of comfort only a mother can give – with the pain she felt for her citizens etched in her face, under the scarf she wore out of respect and solidarity – as she held Muslim women in her arms.

For the first time, Friday Prayers were broadcast live on New Zealand TV, during a service held one week later, in Hagley Park. Community and countrywide leaders joined Jews and various Christian congregations, together with other faith groups, and those not affiliated with any religion, in prayer and providing practical support.

And the world watched – this is how we fight hate and fear in this city – we fight with love, kindness, comfort and compassion – which is love in action. We’ve already been through so much, we know how to pull together and support each other in community. A practical, compassionate community is a healing community. Other continuing acts of comfort include assistance with house-work, providing continued financial support and transport as needed, and at times, sitting, listening, looking at family photos or videos, and even crying together.

Lest We Forget the Victims who Survive

Victims sometimes have a long process to go through, before they can be called survivors. When we remember that not all victims die, and not all survivors live, we remember to be human first – not ethnic, not gender, not nationalistic, not religious – human. We have learned that the comfort we receive is the comfort we can share with another, and how important it is, then, to give and receive comfort – and to ask for it, when we need to.

We find value in sharing our lessons learned through suffering, to assist another, and so it’s vital we heal ourselves, and build resilience, to the very best of our ability, and with professional assistance as necessary.

Every instance of loss and grief is unique, and it’s healthy to be kind to ourselves, and to treat ourselves at least as kindly as we tend to treat others. When we feel compassion for another and act on it, we are sharing love in action. Lest we forget – there are so many survivors of so many forms of trauma. Respectful love is the key to our shared humanity.

If this article has raised issues of trauma or grief for you, please contact:

- Your local doctor – for referral to a few, free sessions of “Brief Intervention Counseling”

- Your Workplace EAP (Employee Assistance Programs)

- Lifeline Helpline – Call 0800 LIFELINE (0800 543 354) or text HELP (4357) for free, 24/7, confidential support

- District Health Board – for emergency – call 0800 CRISIS RESOLUTION

- Check with WINZ for available support if you are on a low income or pension

- OR – watch – The three secrets of resilient people | Dr Lucy Hone | TEDxChristchurch 2019 | www.youtube.com/watch?v=NWH8N-BvhAw

About the Author

- Naomi March, M.A.(2016) has a bachelor’s degree in teaching, and a Master of Arts degree in Pastoral Leadership, with special emphasis on pastoral care to women – in the workplace, society, and the home. Her studies included Crisis Intervention, and Grief Recovery. Email: conversation.corner.chch@gmail.com