CONVERSATION CORNER

by H. Naomi March, M.A.

Celebrating Communication

Last month, we considered the benefit of understanding personal history – through contemplating our ancestors’ and parents’ journeys – hoping to increase our respect for those gone before, and improve our relationship with those still living. Listening to our elders helps close the generational gap, but do we even speak the same language as them, or is there something missing, something lost in generational translation?

Celebrating the Beauty of Language

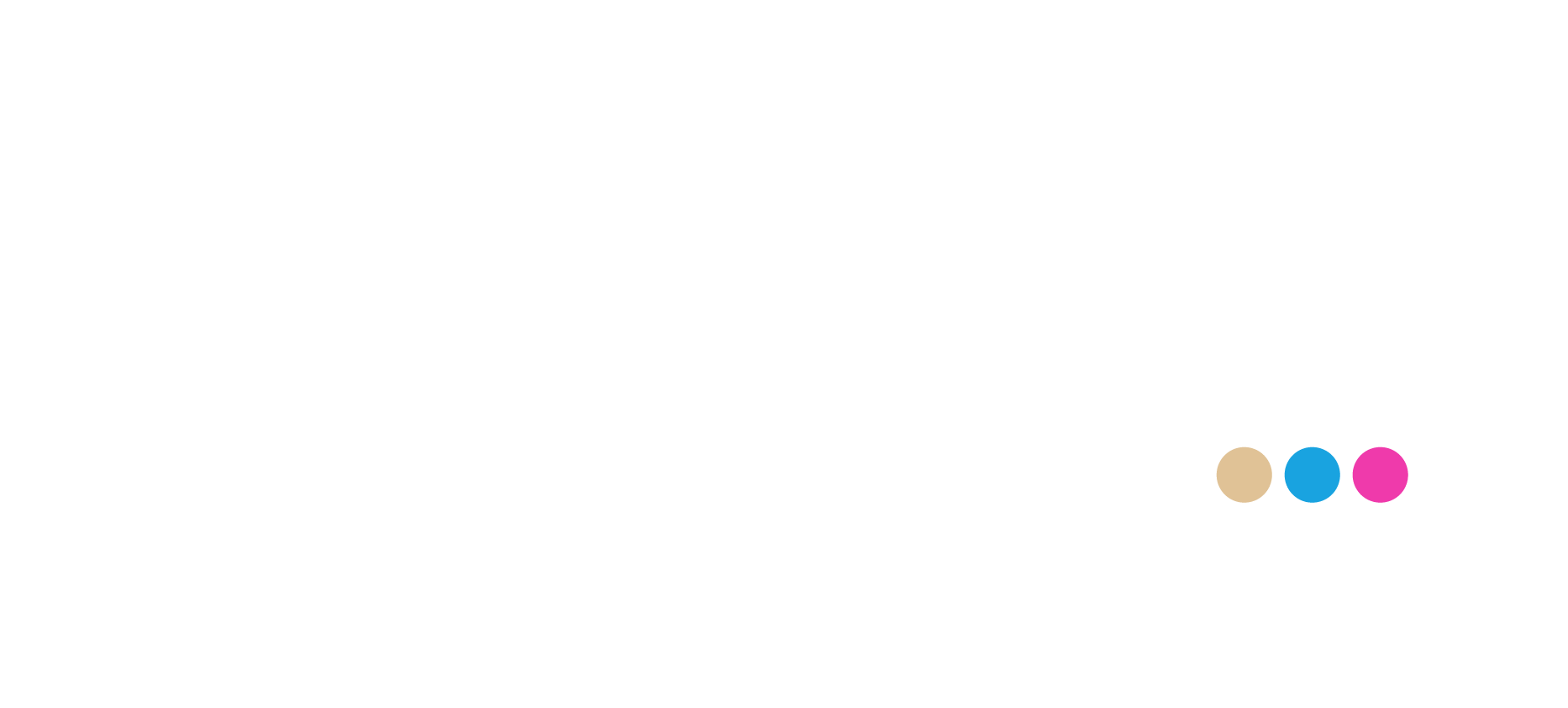

Part of China’s beauty, to me, is its language – not just visually – ‘pictographs’ joined together in different combinations to make ‘characters’ with specific meaning. When painted in the traditional method of ink and brush, these exquisite characters look like works of art.

Chinese Character – “Fu” –means Blessings / Prosperity

Chinese Character – “Fu” –means Blessings / Prosperity

Added to this is the beauty of its sound, and Mandarin Chinese sounds musical to me. Each character must be spoken accurately – using one of four tones – so as not to change the meaning, e.g. you may not want to call your Mum (妈 – Mā) a horse (马 – mă.) And if you are communicating with elders in Chinese, you do not want to call your maternal grandmother your paternal grandmother – easier in English – “Grandma” covers it all. Then there are aunties and uncles and brothers and sisters – all with specific characters.

Growing up in mid-century New Zealand (NZ), I had ‘courtesy Aunts’ – my Mother’s friends who were closer than the neighbours we called ‘Mrs. Smith,’ but not on given-name basis, because – children at that time were not considered adults’ peers. While teaching in China in the mid-1990s – a Chinese English teacher would visit me with her little daughter, who greeted me with, “Ni hao, Ayi” – “How are you, Auntie?” But she was not just addressing me as a ‘courtesy Aunt’ – she was saying, “How are you, my mother’s sister?” Memories of that level of respect and belonging still touch me deeply, decades later.

Gu-Gu means my father’s sister, and I have been lovingly called that, too. I was also called insulting things by people I did not know, which stung – language can also be cruel.

English doesn’t carry the visual beauty that Chinese does, but some of the sounds are exciting: Onomatopoeia – words sound like the object or action, e.g., “splashing” around puddles in gumboots, or, “crunching” through crisp, autumn leaves on the lawn; alliteration always amuses; poetic rhyme and meter (rhythm) is enjoyable.

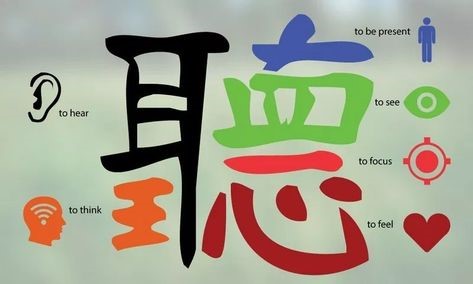

A page from the 1611 edition of the King James Version of the Bible shows the original typeface and layout. c.1611 Usage Terms – Public Domain (USA)

A page from the 1611 edition of the King James Version of the Bible shows the original typeface and layout. c.1611 Usage Terms – Public Domain (USA)

Shakespearian English has a sound of its own, as does the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, translated into English (1611). This language is powerful and poetic, and especially beautiful when read aloud by theatre-trained, British actors. These historic words seem to convey more meaning than the simple words we use today, 400+ years later. Some English words now mean the total opposite – no wonder we sometimes struggle to communicate with our elders.

Celebrating Simplicity

As a 7-year-old, my mother could read a newspaper with understanding. Any words she didn’t know, she would “sound-out” and on hearing the sound, recognized the word and its meaning. To understand a language in its newspaper requires an extremely high level of literacy, e.g. to read a Chinese newspaper would require committing to memory 5,000 characters – and all the combinations of pictographs – no phonics here, to help.

When I was relief-teaching in the early-2000s, 7-year-olds couldn’t spell, or read what they had written the week before, with made-up language they were encouraged to use, during the “Whole Language” fad in Australasia at the time. The Chinese characters used in Singapore and China have been simplified, making it difficult to read older texts, or communicate in writing with Chinese in other countries who prefer the more traditional characters. Are we as nations “dumbing-down” our languages? Does this more simplistic approach make communication, literacy, and literary art, easier or more limiting?

RadioNZ reported (2018) that 40% of NZ adults are struggling with daily-living-levels of reading, and testing 10-year-olds in December 2017, placed us 33rd out of 50 participating countries. Teaching grammar and routine drills are still practiced in China, and I suspect what I observed there, both in English and Chinese classes, is making a big difference in their literacy levels – UNESCO (2018) reports 98.78% literacy for both males and females aged 15-24.

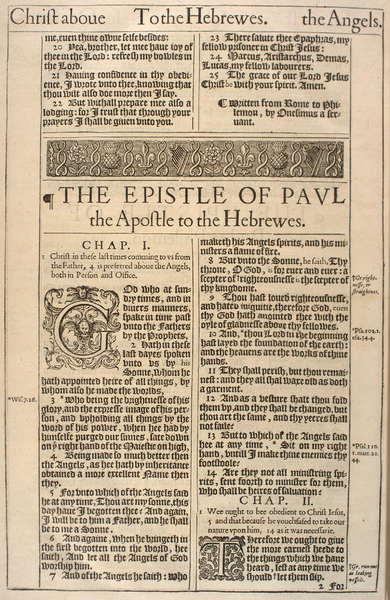

马马虎虎 (mǎ ma hū hū) – i.e. “horse-horse tiger-tiger” gets somewhat lost in translation with the English idiom, “so-so”

马马虎虎 (mǎ ma hū hū) – i.e. “horse-horse tiger-tiger” gets somewhat lost in translation with the English idiom, “so-so”

Celebrating Multi-lingual Literacy

Often, nuance is lost in translation. Let’s encourage multi-lingual learning for children – much easier at their age, and helpful to brain-development. Adult classes are available, and Chinese is back on my ‘Bucket List’ after my recent return-trip.

In “The Truth About Dementia,” (2016) Angela Rippon (then aged 71) interviewed Neuroscientist Dr Thomas Bak – while attending Chinese classes together. His research found that learning at least one other language delayed dementia by four years – a better result than medications were providing.

Another reason to celebrate multi-lingual learning is Tourism. This does more than bring money into NZ; it supports friendships, which bring peace and prosperity to people.

Being hospitable to visitors in their language is a special experience – one I appreciated during my travels in Europe in the early-1980s. Without individuals who had learnt English, I – in my mono-lingual ignorance – would have experienced some extremely difficult times. Their kindness endeared me to them and their nations.

Finally

Personally, I find the Chinese language beautiful to look at – a work of art when skillfully painted with brush and ink, and Mandarin sounds like music to me – hearing it daily, while living and working in China.

Advantages to learning Chinese include delaying dementia, and building the relationship established when we reach out to understand others in the language they prefer.

English also sounds exquisite, especially older vocabulary and poetic forms of the past. Using them can help us communicate more effectively with our elders. Perhaps reading a Shakespearean sonnet, or the KJV of Psalm 23 next visit, would rekindle memories, or provide comfort.

It is through language that we attempt to express ourselves and understand each other. I believe offering empathy and hospitality to others, in ways they are familiar with, creates connections worth celebrating.

About the Author

H. Naomi March, M.A. (2016) has a Master of Arts degree in Pastoral Leadership, with special emphasis on pastoral care to women.

Naomi has traveled through many countries, and lived and worked in China in the mid-1990s. Naomi still delights in finding diversity in people and their places, music and culture.

As an Adult Educator, Naomi is currently writing her series of seminars into book-workbook formats – specializing in “growing up, not growing old,” including health and financial issues in the senior years.

E: conversation.corner.chch@gmail.com