By Nicholas Agar

Wherever one looks – the media,political leaders’ rhetoric, or online discussions – one finds a bias toward bad ideals. This is not to suggest that we – or most of us – endorse, say, racism, misogyny or homophobia, but rather that we grant them efficacy. We believe that extremist ideals must be combated, because we implicitly consider them potent enough to attract new adherents and contagious enough to spread.

At the same time, we tend to take positive ideals less seriously, instinctively disbelieving that it is possible to make meaningful progress toward closing the wealth gap or ushering in a zero-carbon economy. Policies proposed to achieve such ethical ends are regarded as unrealistic non-starters, and the politicians who endorse them are regarded suspiciously or dismissed out of hand.

Taken together, our biases lead us to cede the motivating power of idealism to the bad guys, when we could be harnessing it for the common good.

During the 2017 New Zealand general election, many commentators mocked the optimistic vision advanced by Labour Party leader Jacinda Ardern as “fairy dust.” Likewise, when US Senator Dianne Feinstein was approached by schoolchildren calling on her to endorse Green New Deal legislation, she dismissed their demands as unrealistic.

“That resolution will not pass the senate and you can take that back to whoever sent you here and tell them,” she said.

Now consider the case of the white supremacist who murdered 51 mosque-goers in Christchurch, New Zealand, in March: We granted his obnoxious ideals efficacy. His stated goal was to reverse “The Great Replacement” of white Europeans by Africans and Middle Easterners, which, he claimed, would also “save the environment.” That is plainly absurd.

And yet, when a 19-year-old murdered one person and wounded three in an attack on a California synagogue in April, we paid attention to the fact that he might have made online references to the Christchurch shooter’s manifesto. In both cases, we openly acknowledge that these men are the ideological offspring of the Norwegian white supremacist and mass murderer Anders Breivik.

We should continue to worry about white-supremacist and other extremist ideals spreading online and resonating with some among us, but if we are going to take the persuasive power of such “influencers” seriously, we should do the same with positive ideals that might at first seem absurd. Sprinkled among Ardern’s “fairy dust” was the hope of eradicating student indebtedness and significantly reducing child poverty. Simply by taking these goals seriously, we can grant them the same kind of efficacy that we already impute to toxic ideologies. If we do not dismiss them out of hand, we can begin to think about how they might actually be realized.

No worthwhile moral ideal is fully achievable. Even in affluent New Zealand, true believers in the effort to end homelessness are setting themselves up for inevitable disappointment.

Imagine a young medical researcher who dreams of curing cancer. By the end of her career, she has pioneered a revolutionary treatment for acute myeloid leukemia. Technically, her dream was not realized, but would she have made the invaluable contribution that she did if she had not embraced the unrealistic dream of curing cancer?Early in her term as prime minister, Ardern promised to halve child poverty within 10 years. Her opponent in the 2017 election, National Party’s Bill English, long rejected targets on child poverty on the grounds that it could not be measured. He eventually committed o a comparatively modest target as a shock election debate tactic.

If Ardern manages to remain in office for another 10 years, I would wager that child poverty would not have been halved. Her promise would not have been kept, but like the disappointed cancer researcher, Ardern would be able to point to efforts that made a measurable difference.

Reducing childhood poverty, like tackling climate change, requires widespread human cooperation and some degree of individual sacrifice. The problem is that it is easier for us to conceive of a technological fix for complex social problems than it is to imagine politicians and citizens uniting around a common cause. And, because we view technological hurdles as superable, we have more resolve — and tend to be more tolerant of failure — when pursuing such goals.

For example, though a fire took the lives of the Apollo 1 astronauts — Edward White II, Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, and Roger Chaffee — NASA did not miss then-US president John F. Kennedy’s deadline for landing on the moon. Likewise, we quietly root for SpaceX chief executive Elon Musk when he fantasizes about colonizing Mars.

Still, we cannot count on some beneficent billionaire to develop a new miracle technology that would save us from climate change. Only genuine cooperation can tackle thatproblem and many others like it. Shared ideals can be powerful motivators, regardless of their moral content. Many among the first generation of Soviet revolutionaries genuinely believed in the vision of a communist utopia free of human exploitation, and they made the necessary personal sacrifices to bring it about.

It was not so long ago that we viewed modern-day Nazis as hopelessly deluded. Their occasional marches were almost a source of comic relief — stories saved for slow news days, alongside the pensioner who bequeaths a fortune to his cat. Now, we have to take Nazis seriously once again; we have to worry about the sacrifices they might be willing to make for an evil cause. Sadly, we have no choice but to accept the perverse efficacy of their ideals; but nor should we ignore the potential power of positive ideals as engines for cooperation and moral progress. We should allow ourselves to indulge some of our more optimistic fantasies. They usually bear at least some fruit — and some fruit is better than none.

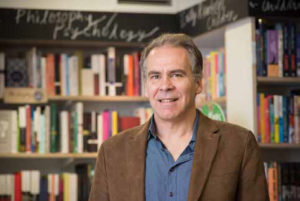

Nicholas Agar is a New Zealand philosopher who has written extensively on the human consequences of technological change.

Copyright: Project Syndicate